1995 Restrospective

Jon Marcus, "Woman, photographer meet 25 years after Kent State," Associated Press, April 24, 1995.

Twenty-five years ago, they made history from opposite ends of a camera lens.

Twenty-five years ago, they made history from opposite ends of a camera lens.

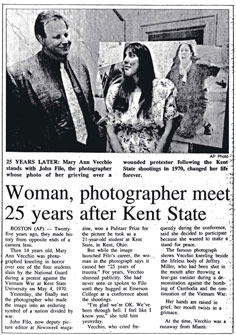

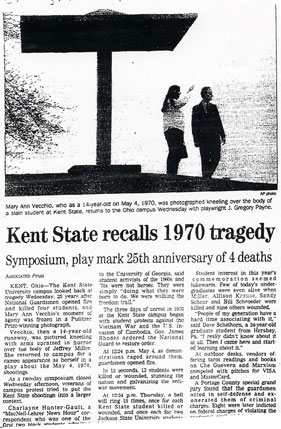

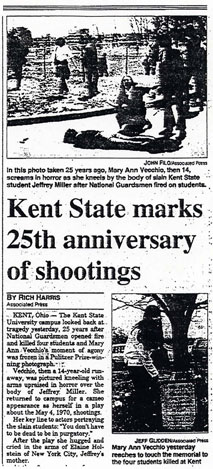

Then a 14-year-old runaway, Mary Ann Vecchio was photographed kneeling in horror over one of the four students slain by the National Guard during a Vietnam War protest at Kent State University on May 4, 1970.

"I hitchhiked right into history," she said. "I couldn't believe that people would kill people over what they thought."

On Sunday, she finally met the photographer who made the image into an enduring symbol of a nation divided by war.

John Filo, now deputy picture editor at Newsweek magazine, won a Pulitzer Prize for the picture he took as a 21-year-old student at the university in Kent, Ohio.

The image launched Filo's career, but Vecchio says it caused her "25 years of trauma." For years, Vecchio shunned publicity. She had never seen or spoken to Filo until they hugged Sunday at a conference about the shootings.

"I'm glad we're OK, we've been through hell. I feel like I know you," she said.

Vecchio cried frequently during the conference at Emerson College, which was attended by about a 100 people. But she said she wanted to be there, to make a stand for peace.

Vecchio cried frequently during the conference at Emerson College, which was attended by about a 100 people. But she said she wanted to be there, to make a stand for peace.

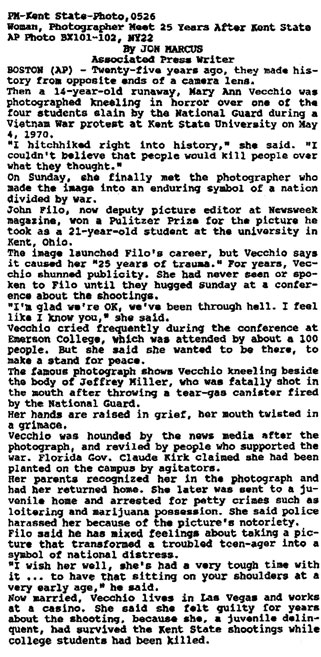

The famous photograph shows Vecchio kneeling beside the body of Jeffrey Miller, who was fatally shot in the mouth after throwing a tear-gas canister fired by the National Guard.

Her hands are raised in grief, her mouth twisted in a grimace.

Vecchio was hounded by the news media after the photograph, and reviled by people who supported the war. Florida Gov. Claude Kirk claimed she had been planted on the campus by agitators.

Her parents recognized her in the photograph and had her returned home. She later was sent to a juvenile home and arrested for petty crimes such as loitering and marijuana possession. She said police harassed her because of the picture's notoriety.

Filo said he has mixed feelings about taking a picture that transformed a troubled teen-ager into a symbol of national distress.

"I wish her well, she's had a very tough time with it ... to have that sitting on your shoulders at a very early age," he said.

Now married, Vecchio lives in Las Vegas and works at a casino. She said she felt guilty for years about the shooting, because she, a juvenile delinquent, had survived the Kent State shootings while college students had been killed.

Filo said he had been talking wildlife photographs off campus when he hurried back for the demonstration.

"I went out that day to look for one good picture," he said.

Filo said he took the film to Pennsylvania to have it developed, because he feared it would be censored in Ohio. He said he received harassing phone calls for two months after the photograph was published.

A $200,000 memorial was dedicated in 1990 on the Kent State campus to the four students slain and the nine injured in the anti-war demonstration.

Rich Harris, "A Second Generation Learns Kent State's Lessons, Associated Press, May 2, 1995.

Thirteen seconds of gunfire. Thirteen students dead or wounded.

Twenty-five years later, Kent State University still remembers the four students killed and nine others wounded by National Guard troops during an anti-war protest on May 4, 1970, with ceremonies and symposiums.

This year, as it has every year, Kent State will memorialize and moralize, hoping to extract something positive from 25 years of tears.

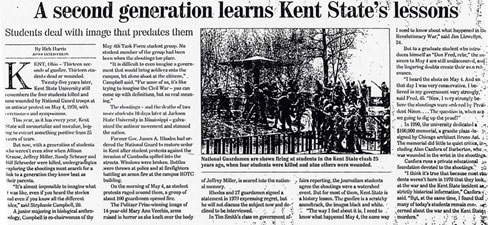

But now, with a generation of students who weren't even alive when Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandy Scheuer and Bill Schroeder were killed, undergraduates exploring the shootings must search for a link to a generation they know best as their parents.

"It's almost impossible to imagine what it was like, even if you heard the stories and even if you know all the different sides," said Stephanie Campbell, 20.

A junior majoring in biological anthropology, Campbell is co-chair of the May 4th Task Force student group. No student member of the group had been born when the shootings took place, and none were on campus in 1990 for the 20th anniversary of the shootings.

"It is difficult to even imagine a government that would bring soldiers onto the campus, let alone shoot at the citizens," Campbell said. "For some of us, it's like trying to imagine the Civil War - you can come up with definitions, but no real meaning.

"But I have never met anyone on this campus who doesn't feel something, even when talking about the barest facts."

The shootings - and the deaths of two more students 10 days later at Jackson State University in Mississippi - galvanized the anti-war movement and stunned the nation.

Former Gov. James A. Rhodes had ordered the National Guard to restore order in Kent after student protests against the invasion of Cambodia spilled into the streets. Shop windows were broken. Bottles were thrown at police and at firefighters battling an arson fire at the campus ROTC building.

On the morning of May 4, as student protests raged around them, a group of about 100 guardsmen opened fire.

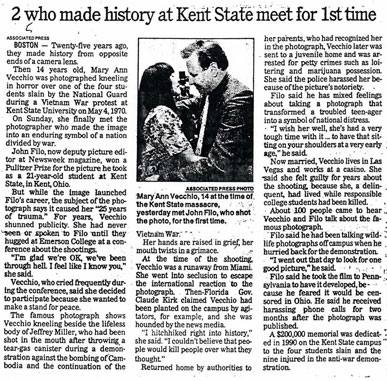

The Pulitzer Prize-winning image of 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio, her arms raised in horror as she knelt over the body of Jeffrey Miller, is seared into the national memory.

Rhodes and 27 guardsmen signed a statement in 1979 expressing regret, but he will not discuss the subject now and declined to be interviewed.

In Professor Tim Smith's class on government affairs reporting, the journalism students agree the shootings were a watershed event. But for most of them, Kent State is a history lesson. The gunfire is a scratchy soundtrack, the images black and white.

"The way I feel about it is, I need to know what happened May 4, the same way I need to know about what happened in the Revolutionary War," said Jim Llewellyn, 24.

"You learn history, maybe so you don't quote-unquote 'repeat it.' Just because I'm a Kent State student, that doesn't mean I need to know more than anyone else about it. ... I really think they jam it down your throat."

But to a graduate student who introduces himself as "Don Fred, relic," the answers to May 4 are still undiscovered, and the lingering doubts create their own relevance.

"I heard the shots on May 4. And on that day I was very conservative. I believed in my government very strongly," said Fred, 45. "Now, I very strongly believe the shootings were ordered by President Nixon. ... The question is, when are we going to dig up the proof?"

In 1990, the university dedicated a $ 100,000 memorial, a granite plaza designed by Chicago architect Bruno Ast. The memorial did little to quiet critics, including Alan Canfora of Barberton, who was wounded in the wrist in the shootings.

Canfora still attends May 4 Task Force meetings and runs a private educational foundation devoted to the shootings.

"I think it's true that because most students weren't born in 1970 that they look at the war and the Kent State incident as strictly historical information," Canfora said. "But, at the same time, I found that many of today's students remain concerned about the war and the Kent State murders."

Canfora said students remain committed to social change.

"Times have changed and the issues have changed, but students remain just as idealistic, just as principled and just as motivated as we were in the 1960s," he said. "The environment, women's rights and freedoms, racism, tuition increases and the current attacks by the Republican Congress on student aid - I think these are the issues of the 1990s that are going to provoke a student movement which may well surpass the 1960s."

Kent State has sponsored dozens of activities in the weeks leading up to the anniversary, culminating this week with a two-day symposium on the "Legacies of Protest," guests such as handgun control advocate Sarah Brady and former senators Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern, and a performance by the folk group Peter, Paul, and Mary.

University President Carol Cartwright thinks students will find the observance relevant.

"Kent has taught the world a lasting lesson about rights, responsibilities and the need for peaceful conflict resolution," she said.

But Zach Brandon, executive director of the undergraduate student senate, says the university must do more to make May 4, 1970, relevant on May 4, 1995.

"This generation can look at the event, but can't feel the same hurt and pain," said Brandon, 22. "I can learn from it. Kent State is a great history lesson on the role of force in a democracy. Those are the type of things we need to look at. But we program for the previous generation. Unfortunately, the students are not going to attend."

Rich Harris, "Kent State Recalls 1970 Tragedy," Associated Press, May 4, 1995.

The Kent State University campus looked back at tragedy Wednesday, 25 years after National Guardsmen opened fire and killed four students, and Mary Ann Vecchio's moment of agony was frozen in a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph.

Vecchio, then a 14-year-old runaway, was pictured kneeling with arms upraised in horror over the body of Jeffrey Miller. She returned to campus for a cameo appearance as herself in a play about the May 4, 1970, shootings.

She had one line to speak to actors portraying the slain students: "You don't have to be dead to be in purgatory."

She had one line to speak to actors portraying the slain students: "You don't have to be dead to be in purgatory."

At the Wednesday afternoon close of a two-day symposium, veterans of campus protest tried to put the Kent State shootings into a larger context.

Charlayne Hunter-Gault, a "MacNeil-Lehrer News Hour" correspondent who was one of the first two black students admitted to the University of Georgia, said student activists of the 1960s and '70s were not heroes. They were simply "doing what they were born to do."

"We were walking the freedom trail," she said.

Three days of unrest on the campus began with student protests against the Vietnam war and the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. Then-Gov. James A. Rhodes ordered the National Guard to restore order.

At 12:24 p.m. on May 4, as demonstrations raged around them, guardsmen opened fire.

In 13 seconds, 13 students were killed or wounded, stunning the nation and galvanizing the anti-war movement.

Vecchio's appearance was for a play by Emerson College Professor J. Gregory Payne. In "Kent State: A Requiem," the four dead students examine the events that led to the shootings.

Vecchio's appearance was for a play by Emerson College Professor J. Gregory Payne. In "Kent State: A Requiem," the four dead students examine the events that led to the shootings.

Vecchio said she received hate mail for years after the shootings. Her line in the play refers to that unwanted notoriety.

At 12:24 p.m. on Thursday, a bell will ring 15 times, once for each Kent State student killed or wounded, and once each for two Jackson State University students killed in a protest 10 days later.

Student interest in this year's commemoration seemed lukewarm. Few of today's undergraduates were even alive when Miller, Allison Krause, Sandy Scheur and Bill Schroeder were killed and nine others wounded.

"People of my generation have a hard time associating with it," said Dave Schelhorn, a 24-year-old graduate student from Hershey, Pa. "I really didn't know about it at all. Then I came here and started learning about it."

At outdoor desks, vendors offering tarot readings and books on Che Guevera and Marxism competed with pitches for VISA and MasterCard.

A Portage County special grand jury found that the guardsmen acted in self-defense and exonerated them of criminal charges. Eight were later indicted on federal charges of violating the students' civil rights, but those charges were dropped.

The wounded students and the families of the dead settled a $ 40 million civil suit out of court in January 1979 for $ 675,000.